Revenge of the Noids!

If the existence of hundreds of strains of kaleidoscopic green, orange, purple, and pink hues with namesakes often referencing bouquets of fruit (Grape Ape, Mimosa, Gelato), candy (TK41 aka White Gushers, Runtz), gas (the legendary Sour Diesel and Chemdawg), dank funk (Blue Cheese), and tongue-in-cheek nods to the act of getting high itself (Amnesia Haze, Trainwreck, Skywalker OG) isn’t proof enough, I hope to spend some time further exploring how cannabis is beautifully complex.

For the sake of keeping this entry to a digestible length, I want to focus on the essential building blocks that create weed’s psychoactive “high” and help deliver benefit diversity cannabis - cannabinoids. These compounds are crucial in providing cannabis’ sense-altering, medical, and therapeutic benefits. Teaming up with terpenes (which provide aroma, taste, and experience boosting properties) and flavonoids (responsible for cannabis’ vivid color palette), cannabinoids help in delivering your specific type and strength of high in a plant-powered combination dubbed the “entourage effect.” While over 100 cannabinoids have been identified in cannabis, I’ll focus on the “Big 6” cannabinoids (THC and its relative “minor cannabinoids”) that are present in weed in the largest concentrations, most responsible for influencing your high, and where research focus has yielded some interesting initial results. Before diving into their powerful and numerous benefits, I think it’s helpful looking a bit more into the biological and chemical structure of the plant itself.

Below is a diagram of the central flowering top of a female cannabis plant (the “cola”) which contains bundles of densely-packed and vibrant nugs.

Simplified cola diagram

The colorful orange hairs decorating the bud, called stigmas, are a crucial part of the female plant’s reproductive system (the pistil) and help collect and retain pollen from male plants. For today’s entry, I want to focus the biology portion on trichomes. If you’ve ever wondered why certain types of flower appear to be covered in a crystalline sugar like patchwork, you’ve discovered trichomes. These resinous glands, which can be found scattered across both flowering portions and leaves of the plant, contain the active compounds in cannabis that come together in the entourage effect to get you high - cannabinoids, terpenes, and flavonoids (which are also found in leaves and seedlings). As a general rule, you can expect trichome coverage to correlate with flower quality and cannabinoid presence. Said simply, the frostier the nug, the stronger and more rich you can expect your cannabis experience to be.

Having spent a little time identifying where cannabinoids are in the plant, let’s dive into their role in modulating our internal endocannabinoid system (ECS). Although not as well known as some human systems, like the sympathetic nervous system that creates biologically-wired “flight or fright” responses to perceived danger, the ECS is crucial for regulating many of our day-to-day functions including memory creation/storage, mood, sleep, appetite regulation, pain processing, and immune function. We produce cannabinoids naturally (so-called endocannabinoids) that interact with cannabinoid receptors to fuel these complex operations. Cannabinoids found naturally in plants like cannabis (phytocannabinoids), and synthesized cannabinoids influence these processes when introduced via heat (vaping/heating for use in edibles) or combustion (smoking) in a process called decarboxylation. In short, the proper amount of heat will remove a carboxyl group (a structure consisting of a carbon atom double-bonded with oxygen and single bonded with a hydroxyl group) from cannabinoid molecular structures to allow absorption and efficacy in the body. Cannabinoids are processed at a few main receptor sites in our bodies, with the most-researched being cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) and cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2). Although they work together, CB1 and CB2 receptors process cannabinoids at different places in the body and for different purposes:

-CB1: Receptors are located primarily in the brain (namely the cortex, basal ganglia, hippocampus, and cerebellum) and connective tissues¹. Location is everything. These parts of the brain are responsible for important tasks like sensory processing, movement/coordination, memory creation/retention, and behavior/executive functioning. When plant-based cannabinoids are introduced at CB1 receptors, they have been found to have impact on these functions via process calibration and dopamine release². For these reasons, it has been hypothesized that the euphoria, creativity, goofy-fogginess and other mental effects that immediately follow cannabis use are a result of action happening at our CB1 receptors. Interaction at CB1 receptors in particular has created significant promise and interest in cannabis’ ability to aid in treating symptoms of PTSD and mood disorders, where patients display excited levels of CB1 activity when untreated³. Michael Pollan, an acclaimed researcher and writer at the intersection of food, plants, biology and society, made a simple but powerful note in his book The Botany of Desire on the power of inducing states of “forgetfulness” in destressing an overloaded ECS and maintaining functional balance: “For it is only by forgetting that we ever really drop the thread of time and approach the experience of living in the present moment, so elusive in ordinary hours”⁴.

-CB2: These receptors, which are less numerous than CB1, are located primarily on tissue in the body’s immune, gastrointestinal, and peripheral nervous systems. For these reasons, CB2 receptors are more closely associated with the body effects of cannabis, namely inflammation reduction and muscle relaxation. The anti-inflammatory effects of cannabinoids⁵ have shown research and anecdotal efficacy in easing pain and swelling associated with chronic conditions like arthritis, IBS, and Crohn’s disease while also reducing nausea⁶ and aiding in pre-sleep relaxation.

"Big 6" Breakdown

〰️

"Big 6" Breakdown 〰️

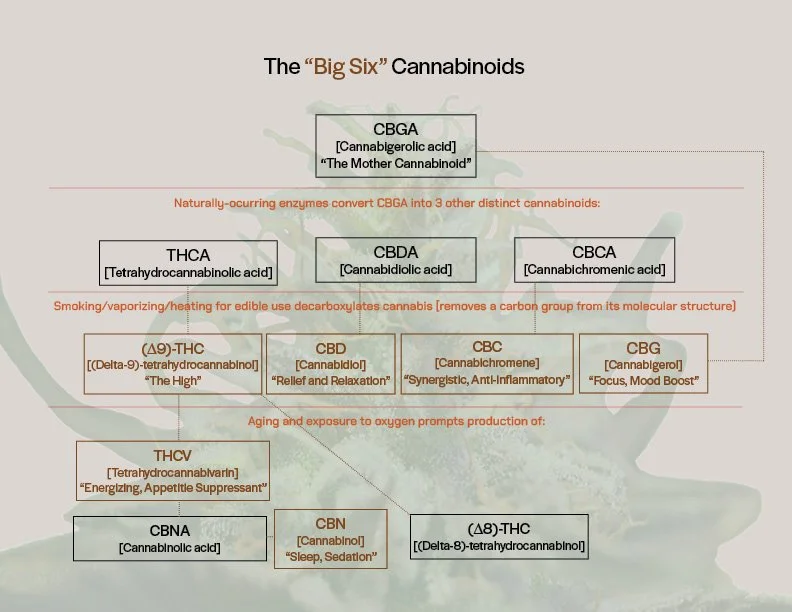

With a basic overview of the endocannabinoid system and its primary receptors, let’s get into “The Big 6” cannabinoids and how they interact with the ECS and each other to get you high and provide relief. Below is a cannabinoid tree that traces the origin of each of the “Big 6” (in brown) within the plant’s chemistry:

A tree of the “Big 6” cannabinoids and their relatives

At first glance, you might wonder why THC (shorthand for ∆9-THC) is so low on the hierarchy. Not to knock the importance of THC in delivering weed’s potent punch, but THC and all other cannabinoids found in cannabis owe their existence to the lesser-known but powerful CBGA, or “Mother Cannabinoid.” Through enzymatic reactions, CBGA is converted into the three precursor acids that spawn the “Big 6” cannabinoids: THCA (the parent of THC), CBDA (the parent of CBD), and CBCA (the parent of CBC). Not until cannabis is decarboxylated (heated for edible preparation/smoked/vaped) do these cannabinoids activate and deliver expected mental and physical benefits. So once you’ve sparked up or waited for your edible to hit, here’s what you can expect each of the “Big 6” to do for you:

∆9-THC: Often shortened to just “THC,”, this cannabinoid is the one most people think of when attributing weed’s haze and hunger-inducing high. And not for no reason - THC is the only cannabinoid that has psychotropic (sense-altering) properties and it is the most abundant one found naturally in cannabis. These factors, as well as a lack of (and restrictions on) significant historical research and product integrations with other cannabinoids, have contributed to THC being the leading factor for both cannabis companies and consumers in assessing product strength and quality. THC’s potency is additionally supported by how it works in the endocannabinoid system: THC binds at the body’s CB1 and CB2 receptors, which helps explain why it creates both mental intoxication and physical relief⁷.

I would be remiss in talking about THC without mentioning similar-sounding relatives like ∆8-THC (“Delta 8”) and THCA, which you may see listed on packaging or in product promotions. The popularity of Delta 8 and THCA flower/edible, as well as related online and mail order services, can be in part tied to their ability to be used cleverly in products and marketing in ways that meet hemp product regulations as outlined in the 2018 Farm Bill. To the letter of the law, any hemp product containing less than .3% ∆9-THC by weight is considered industrial hemp, and does not need to be regulated closely like cannabis (>.3% THC). Delta 8 produces similar effects as THC, although it is around 30% less potent as it has weaker cannabinoid receptor binding capacity⁸. Delta 8 is present in cannabis in relatively small amounts naturally and is commonly synthesized from raw hemp to create a distillate that can be added to edible products or applied directly onto non-psychoactive hemp flower to create smokable high-inducing Delta 8 nugs.

While Delta 8 is a cannabinoid that has psychotropic effects (it is THC after all), THCA is not. THCA, as a precursor to THC, does not have any proven perception-altering effects on its own. Once it is vaped/smoked/consumed in edible form the body will process and react to THC. Products advertised as “THCA flower” that will get you “high” are more or less innovative ways to sell hemp that has less than .3% naturally-occurring THC and plenty of THCA which will get you high once sparked up. For products promising a THCA “high,” those stats face additional concerns with testing manipulation, as cultivators can use test timing and strain selection to their advantage. Since cultivators have a higher standard (<.3% THC + THCA) than retailers (<.3% THC) under the Farm Bill, there can be incentives to select strains that take a while to present THCA, such that the cultivator passes the test early in the grow and can deliver a potent THCA product at retail once the flower matures⁹.

THCV: With a “V” for varin - a class of cannabinoids that has a three-carbon structure to aid in receptor binding - THCV is a special cannabinoid. Research has yielded strong implications for THCV’s ability as an appetite suppressant¹⁰ and to aid in neuroprotection (against diseases like Alzheimer's, Multiple Sclerosis, and Parkinson’s). THCV’s energizing and motivating effects also make it a helpful cannabinoid for people who struggle with PTSD, anxiety/panic attacks, or mood regulation¹¹. Given its uplifting properties, you can expect to find THCV in larger concentrations in sativa (“euphoric, upbeat”) strains as opposed to indica (“relaxing, sedating”) strains. Note: indica and sativa designations have proven to not be very precise in describing a strain’s effects, compared to analysis of terpenes and cannabinoids. More on this topic in the next entry!

CBN: This “sleepy” cannabinoid is created as THC is broken down by age and exposure to heat, lights, and air. Although THC may be the most prevalent cannabinoid, CBN was the first to be discovered, as the founding team likely sampled an older bud when doing their work. Exciting studies like those conducted by FloraWorks - a biotech company specializing in cannabinoid research and applications - etch in stone CBN’s ability to create more restful sleep. In this study, participants who took a 50mg dose of CBN had significantly better sleep compared to a placebo, and had slightly better sleep compared to taking nightly melatonin¹². Given how important sleep (and solving sleep-related issues) is to a lot of people, it’s not surprising that cannabis market researcher BDSA has seen usage grow, with CBN edible sales increasing by 66% between Q1 2022 and Q4 2023¹³.

CBD: The “soothing” and second most abundant (and popular) cannabinoid. Unlike THC, which binds strongly to CB1 and CB2 receptors, this compound binds pretty weakly to both and doesn’t compete for space in terms of uptake. Instead, it is regarded as a negative allosteric modulator which impacts how other cannabinoids bind to receptors and how information flows between neurons, particularly for our serotonin and opioid/reward systems¹⁴. Since CBD does not compete with THC in the body, they can be processed in ways that work synergistically. Studies have confirmed that THC in combination with CBD significantly reduces pain and improves sleep in cancer patients, relative to a placebo and THC alone¹⁵. CBD’s method of activation and calming properties are often sought out for anxiety/pain/sleep management and may prove beneficial in adjusting reward and motivation systems in patients with addictive behaviors and substance use disorders¹⁶.

CBC: The “pain relieving and synergistic” cannabinoid. CBC is thought to be effective at reducing aches and inflammation as it bonds strongly to pain receptors while its weak binding capacity to CB1 receptors leave it with few mental effects in isolation. CBC’s potential ability to fight pain and depression are in large part due to its ability to forge strong alliances with other cannabinoids. Studies have shown that CBC taken in combination with THC reduces pain and inflammation more than either taken separately,¹⁷ while CBC in use with THC and CBD has been found to potentiate relief of depression symptoms¹⁸.

CBG: The “uplifting and neuroprotective” cannabinoid (my personal favorite besides THC). CBG’s origin is a little different than the other “Big 6.” As CBGA is converted into THCA, CBDA, and CBCA in chemical reactions, any leftover CBGA converts to CBG when decarboxylated. For this reason, CBG is usually found in relatively small levels naturally, but cultivators hip to its powerful effects (like specialist growers Atlantis Cannabis Company and Horn Creek Hemp) have been knocking it out of the park with federally legal high-CBG strains. What effects you ask? For starters, CBG is the only cannabinoid that has been found to stimulate new cell growth to aid against neurodegeneration in mice¹⁹ and may have promise as a cancer cell growth inhibitor²⁰. CBG also interacts with a specific cannabinoid in our internal endocannabinoid system called anandamide, which plays a key role in stimulating motivation/focus and appetite, and reducing pain²¹. The release of compounds like anandamide have also been posited to be part of the inspiring exercise experience known as the “runner’s high.” Since CBG has such potential for relieving day-to-day and chronic issues, research is currently underway to understand its presence and extraction potential in the Woolly Umbrella plant, a legal perennial that grows in the mountains of Zimbabwe and South Africa²². Data suggest the Woolly Umbrella may contain above 4% CBG by weight, which is more than 4x what is found in the average cannabis sample²³.

While there is a vast world of cannabinoids to explore, the “Big 6” are a great starting point to understanding the benefits that they can bring, especially as these are most likely to be used in products in the market today. As cannabinoid research, packaging information, and product formulations continue to evolve, keep an eye out for more cannabinoid-forward products aimed at delivering targeted effects. According to Jerry Griffin, VP of Sales and Marketing at BayMedica - a manufacturer of cannabinoids for commercial applications - the minor (non-THC) cannabinoid market grew by $126 million in 2023¹³. If what we know about the “Big 6” and others continues to be studied and applied at scale, I don’t see growth in these product types shrinking any time soon. Whether you’re a “noid head” or just curious about non-THC cannabinoids, here are a few of my favorite cannabinoid-forward brands and products that you can get in NYC dispensaries right now:

-Ayrloom: Huge selection of THC + CBD/CBN/CBC/CBG/THCV combinations across vapes, edibles/drinks, balms, and tinctures

-Grön: “Pearl” gummy orbs that blend THC with curated selections of CBD/CBC/CBG/CBN

-1906: Microdosed cannabinoid blends in easy-to-pop herbal drops

-Weekenders: THC+CBD pre-rolls in varying ratios (4:1, 1:2, 1:1)

-Miss Grass: “Half Times” line, 1:1 THC:CBD pre-rolls

-Protab: higher-dose combination (THC + CBD, THC + CBD + CBG) and single-cannabinoid (CBD, CBDA, CBG) edibles

-Off Hours: THC + CBG/CBD/CBN/THCV edibles in awesomely psychedelic packaging

Sources:

1 - Mackie, K. “Distribution of cannabinoid receptors in the Central and peripheral nervous system.” Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, pp. 299–325, https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-26573-2_10.

2 - Dazzi L;Talani G;Biggio F;Utzeri C;Lallai V;Licheri V;Lutzu S;Mostallino MC;Secci PP;Biggio G;Sanna E; “Involvement of the Cannabinoid CB1 Receptor in Modulation of Dopamine Output in the Prefrontal Cortex Associated with Food Restriction in Rats.” PloS One, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24632810/. Accessed 1 May 2024.

3 - Neumeister, A, et al. “Elevated brain cannabinoid CB1 receptor availability in post-traumatic stress disorder: A positron emission tomography study.” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 18, no. 9, 14 May 2013, pp. 1034–1040, https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2013.61.

4 - Pollan, Michael. The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s Eye View of the World. Random House, 2001.

5 - Turcotte, Caroline, et al. “The CB2 receptor and its role as a regulator of inflammation.” Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, vol. 73, no. 23, 11 July 2016, pp. 4449–4470, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2300-4.

6 - Stith, Sarah S., et al. “The effectiveness of common cannabis products for treatment of nausea.” Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, vol. 56, no. 4, 7 Apr. 2021, pp. 331–338, https://doi.org/10.1097/mcg.0000000000001534.

7 - Raypole, Crystal. “Endocannabinoid System: A Simple Guide to How It Works.” Healthline, Healthline Media, 17 May 2019, www.healthline.com/health/endocannabinoid-system#how-it-works.

8 - “Cannabinoids.” Trichome Analytical, 16 Dec. 2020, trichomeanalytical.com/cannabinoids/#8thc.

9 - Sacirbey, Omar. “Not All Agree That THCA Meets Definition of Hemp.” MJBizDaily, 19 Mar. 2024, mjbizdaily.com/does-thca-adhere-to-legal-definition-of-hemp/.

10 - Abioye, Amos, et al. “Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV): A commentary on potential therapeutic benefit for the management of obesity and diabetes.” Journal of Cannabis Research, vol. 2, no. 1, 31 Jan. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s42238-020-0016-7.

11 - “THCV.” Cresco Labs, 3 July 2019, www.crescolabs.com/cannabinoids/thcv/.

12 - “Floraworks Announces Scientific Breakthrough in Natural Sleep Aids: First-Ever Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial Discovers CBN Effective for Sleep.” Yahoo! Finance, Yahoo!, finance.yahoo.com/news/floraworks-announces-scientific-breakthrough-natural-110000592.html?guccounter=1. Accessed 1 May 2024.

13 - Rudolph, Garrett. “The Edibles Issue: Minor Cannabinoids Rejuvenate Edibles Category.” Marijuana Venture, 17 Apr. 2024, www.marijuanaventure.com/minor-cannabinoids-rejuvenate-edibles-category/.

14 - Capodice, Jillian L., and Steven A. Kaplan. “The endocannabinoid system, cannabis, and Cannabidiol: Implications in urology and Men’s Health.” Current Urology, vol. 15, no. 2, 28 May 2021, pp. 95–100, https://doi.org/10.1097/cu9.0000000000000023.

15 - Whynot, Erin G., et al. “Anticancer properties of cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and synergistic effects with gemcitabine and cisplatin in bladder cancer cell lines.” Journal of Cannabis Research, vol. 5, no. 1, 4 Mar. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1186/s42238-023-00174-z.

16 - “Can CBD Treat Opioid Use Disorder?” National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, heal.nih.gov/news/stories/can-cbd-treat-opioid-use-disorder. Accessed 1 May 2024.

17 - DeLong, Gerald T., et al. “Pharmacological evaluation of the natural constituent of Cannabis Sativa, cannabichromene and its modulation by Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol☆.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, vol. 112, no. 1–2, 1 Nov. 2010, pp. 126–133, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.05.019.

18 - El-Alfy, Abir T., et al. “Antidepressant-like effect of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis Sativa L.” Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, vol. 95, no. 4, June 2010, pp. 434–442, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2010.03.004.

19 - Valdeolivas, Sara, et al. “Neuroprotective properties of Cannabigerol in Huntington’s disease: Studies in R6/2 mice and 3-nitropropionate-lesioned mice.” Neurotherapeutics, vol. 12, no. 1, Jan. 2015, pp. 185–199, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-014-0304-z.

20 - Lah, Tamara T., et al. “Cannabigerol is a potential therapeutic agent in a novel combined therapy for glioblastoma.” Cells, vol. 10, no. 2, 5 Feb. 2021, p. 340, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10020340.

21 - Strains with CBG & CBN Are More Expensive, but Are They Worth It? | Docmj, docmj.com/strains-with-cbg-cbn-are-more-expensive-but-are-they-worth-it/. Accessed 1 May 2024.

22 - Hammell, Robert. “The Woolly Umbrella a Natural Unexpected Source of Cannabinoids.” Extraction Magazine, 9 Apr. 2024, extractionmagazine.com/2024/04/09/the-woolly-umbrella-a-natural-unexpected-source-of-cannabinoids/.

23 - Ohwovoriole, Toketemu. “What Is Cannabigerol (CBG)?” Verywell Mind, Verywell Mind, 12 June 2023, www.verywellmind.com/cannabigerol-cbg-uses-and-benefits-5085266.